Once the cameras are off and the shoot is over, the real work begins. That’s when you turn all that raw footage into a full-fledged film. Editing is an essential step of the film post-production process, and how it’s done can make or break a movie. Luckily, editors through history have created an arsenal of techniques that anyone can use to splice movies together, each with its own unique purpose in storytelling.

What is a cut in film and TV?

Video cuts (also called movie cuts or film cuts) are transitions in films and videos that allow filmmakers to weave multiple camera shots together. These transitions play a key role in visual storytelling, and it’s on the editor to choose the best types of cuts to serve the film’s core narrative.

The term “cutting” dates back to the days of celluloid film, when directors and editors would spend their post-production time literally slicing and splicing strips of film to create smooth transitions between shots and scenes.

In the modern film industry, video editors no longer wield utility knives. They hone their editing technique on the computer, where fully featured editing software can cover all the major cuts used by professional editors.

10 different types of video cuts

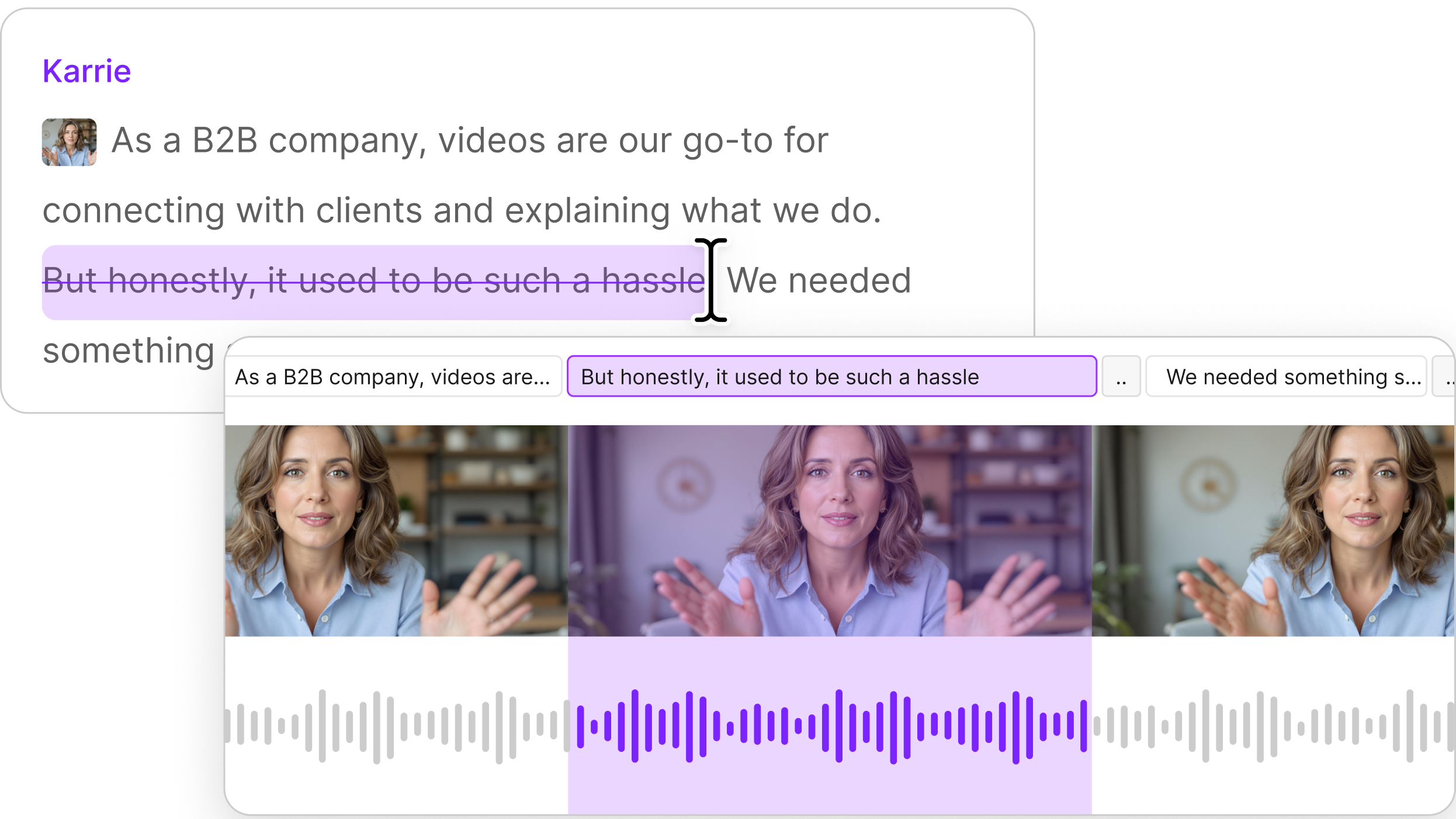

Today’s video editing software makes adding and editing cuts simpler than ever before. Whether you’re editing your video project in a legacy program like Adobe Premiere or an AI-driven platform like Descript, you’ll need working knowledge of the basic types of cuts available so your videos can look professional and tell a story the way you want them to.

1. Standard cut

The standard cut, also known as a hard cut, is a classic editing technique where one scene goes directly to the next with no extra transition. You might see the term 'smash cut' used in scripts for a more abrupt, jarring version of this technique, often indicating a sudden shift in tone. You can see an assortment of smash cuts in Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained(2012) in a dining room scene where ruthless slave owner Calvin J. Candie (Leonardo DiCaprio) loses his mind over deception from Django (Jamie Foxx) and Dr. Schultz (Christoph Waltz).

2. J-cut

A J-cut is a classic technique where the audio from the next clip overlaps with the video of the previous clip. For example, imagine you have two video clips: Clip A and Clip B. In a J-cut, the audio from Clip B will begin playing before the video from Clip A concludes. This type of editing is known as a split edit. This cut is named for the way it looks in a video editor: the new audio track sticks out to the left of the new video track above it to resemble the shape of the letter J. You can see a J-cut in action in a scene from Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004) where a tense sequence with Joel Barish (Jim Carrey) and Clementine Kruczynski (Kate Winslet) ends with the overlay of audio from young children playing outside.

3. L-cut

An L-cut is the opposite of a J-cut, and it, too, qualifies as a split edit. It cuts to new visuals while the audio from the previous shot continues. So if you had Clip A and Clip B, you would continue audio from Clip A while cutting to the video of Clip B. In a famous L-Cut from the action film Predator (1987), a petrified scream from Al Dillon (Carl Weathers) continues into the next visual clip of soldiers elsewhere in the jungle.

4. Jump cut

Jump cuts are named for the fact that they “jump” ahead or backward in a film’s chronology. They indicate the passage of time. One of the most famous uses of the jump cut occurred in Jean Luc-Godard’s first film Breathless. What could have been a lull in the film’s momentum is brought back to life by keeping only the most interesting bits of dialogue. It makes the audience feel as though they’re moving through time faster. His use of jump cuts popularized the technique for the rest of the film industry.

5. Cross-cut

Cross-cutting is the act of cutting back and forth between two sequences. You can cross-cut between a pair of scenes, or you can cross-cut among multiple scenes in multiple locations. You can even cross-cut between two events taking place in the same physical space and on the same exact timeline. In the 1990 horror-thriller Misery, director Rob Reiner uses cross-cutting to build suspense as novelist Paul Sheldon (James Caan) frantically wheels his wheelchair through the house while his captor Annie Wilkes (Kathy Bates) walks up the front path to the door.

6. Parallel editing

Parallel editing uses the same back-and-forth technique found in cross-cutting, but its purpose is slightly different. Specifically, parallel editing does not necessarily strive for the illusion that two scenes are happening simultaneously. Instead, it intercuts to draw thematic comparisons. Alfred Hitchcock uses parallel editing masterfully in his opening scene of Strangers of a Train (1951). Showing only his characters’ legs and feet, he cuts back and forth between his two titular “strangers” arriving at a train station in taxis, exiting, walking through the terminal, boarding the train, and finally sitting down across from one another. The parallel editing doesn’t end until the characters are face-to-face.

7. Match cut

A match cut connects two scenes by showing a common element in back-to-back shots. An example is one scene ending on the image of someone looking at a globe on a desk and the next scene showing astronauts viewing planet Earth from orbit. One of the most dramatic (and imitated) match cuts in all of cinematic history occurs in Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 sci-fi space opera 2001: A Space Odyssey. A prehistoric ape tosses a bone in the air and then the film seems to jump roughly one million years into the future as the skybound bone becomes a spaceship in flight.

8. Cutting on action

Cutting on action means inserting a cut in the middle of an action sequence, like when one person throws a punch and we cut to the point of view of their victim watching the fist hurtle toward them. For a multi-clip example of cutting on action, check out the scene in The Natural(1984) where Roy Hobbs (Robert Redford) strikes out a feared hitter nicknamed “The Whammer” at a county fair. The same single pitch involves six different cuts that show seven film clips — a clinic in seamless cutting from director Barry Levinson and editor Stu Linder.

9. Cutaways

A cutaway is a brief visit from a principal scene to a secondary scene that’s only tangentially related. Cutaways are popular in comedy since they can reveal additional information that makes the main scene even funnier. You can find a hilarious cutaway sequence in Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery, the Jay Roach-directed 1997 spy comedy starring Mike Myers. In a suspense sequence, Austin Powers (Myers) has to turn around an electric cart in a narrow tunnel. He attempts to do a 3-point turn but has little luck. The scene then cuts away to Dr. Evil (also Myers), who is about to execute the final stages of his diabolical plot, which only Austin Powers can stop. The film then cuts back to Austin Powers, now completely stuck in his electric cart with no way to turn around. The cart gag is funny enough by itself, but the cutaway makes it a comedy classic.

10. Montage

A montage is a series of intercut scenes that provides a narrative, often without dialogue. By cutting back and forth among various sequences, directors and editors can reveal how multiple storylines converge into a unified whole. Montage sequences often turn up when a character undergoes a transformation — whether literal or metaphorical. A great makeover montage can be found in the 1995 comedy Clueless where Cher (Alicia Silverstone) helps her friend Tai (Brittany Murphy) remake her image. As the camera cuts around to various scenes of the high schoolers trying on clothes and dying Tai’s hair, Jill Sobule’s song “Supermodel” provides a fitting underscore.

When to use each type of cut

With so many types of editing in film, it can be hard to decide what type of cut to use with what type of footage. Here are some ideas to guide your editing process.

Also remember that cuts aren’t the only way to transition between shots. Dissolves, fades, wipes, and other transitions can sometimes add emotional resonance or signify the passage of time. Use them sparingly and purposefully—many editors rely on these transitions to soften abrupt changes or highlight thematic shifts.

- Use jump cuts to speed ahead without dialogue. Sometimes the best way to show the passing of time is to do so silently. Jump cuts of the same scene, room, or even a clock face can quickly establish that time has passed and the narrative has sped ahead by minutes, hours, or days.

- Use match cuts to aid with difficult transitions. If you are cutting between two scenes with seemingly little in common, look for a related element between the scenes to anchor a match cut. This could be a similar shape or color, a matching prop, or even a sound and a reaction to a similar sound.

- Use a J-cut when a script calls for pre-lap dialogue. If you see a script where a character has (PRE-LAP) next to their name, this means their audio track should enter before that visual transitions to the next shot. In other words, the writer is calling for a J-cut.

- Use cross-cutting for phone conversations. When a script intercuts between two people on the phone with one another, use cross-cutting to show both of their perspectives. This way you can focus on key reactions from each character.

4 key rules of video cuts for directors and editors

Well-placed video cuts are essential to the post-production process, but they can still be overused. Use these four tips to make your video cuts as precise and effective as possible.

- Sometimes you just need to let the action play out. Cutting is a great tool for a director, and some directors favor short, pithy scenes that quickly jump cut to something new (looking at you, Christopher Nolan). But long scenes also have a purpose in cinema. Watch a film by Kubrick, Coppola, or Scorsese to see how much emotional heft and simmering tension can come out of a single shot that lasts a full minute, or even longer. These directors certainly use jump cuts for transitions, but they tell their stories via long, luxuriating shots that play out like a live theater production.

- Make sure your action cuts are punctuated by sound. Action cuts that show multiple angles of the same action sequence make for an enthralling scene. These types of edits are great, but they only work if sound reliably punctuates the visuals. As you work with your raw footage, make sure you have all the sound effects you need to make your action cuts compelling and believable. If you’re cutting to a bowling ball knocking over pins, make sure it syncs up with the precise sound of impact and toppling pins. If you show a character jumping and then cut to them hitting the ground, make sure it combines with a satisfying “thud.”

- Use match cuts to organically show thematic overlap. Match cuts and parallel editing can reveal thematic throughlines to an audience. By weaving back and forth between scenes, directors can show thematic parallels between different characters performing different actions in different locations. A word of warning: This only works when you really do have a thematic throughline. If you’re working with a pair of scenes that don’t actually have thematic overlap, you don’t need to force it.

- Storytelling comes first. Moviegoers don’t attend film screenings to watch an editing clinic. They want to watch stories on screen. Make sure your edits serve the story and never compete with it. Choose cuts that advance the storytelling over those meant to purely show off your editing chops. Who knows? Maybe the story will actually call for some post-production virtuosity. But if it doesn’t, save your pyrotechnics for a future project.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cut out parts of my video in Descript?

Use Descript’s text-based editing or the timeline to highlight and delete the unwanted sections. You can also place the playhead at precise points, use the blade tool if you need more control, and remove the clips you don’t want.

What are motivated cuts in editing?

A motivated cut is when you cut for a clear reason—like revealing a reaction or a significant detail—so each edit serves the story and doesn’t jar the viewer. For example, you might cut to show an object another character just mentioned, giving the audience new visual context.

What are cutaways, and how do they add context?

Cutaways briefly shift focus from a main scene to related visuals that highlight details, reactions, or location. They enrich a sequence by adding background info, comedic pauses, or emphasis on a specific part of the story.